Built different

on the need for better representation in clinical trials

Are you like other girls? I didn’t think so. Likewise, people with the same diseases differ from each other beyond having a brat or demure/mindful summer. Variance in age, environment, ethnicity, gender, and genetics means people may respond differently to the same treatment. If you don’t know how a drug goes from the lab bench to you, it’s through clinical trials. These are studies on new medicines, vaccines, or devices to see if they work safely in humans. After animal lab tests and before drugs can be marketed and sold, researchers assess

if the drug is safe + how to best deliver it/dose it so it doesn’t harm you (Phase I)

if the drug works, like at all (Phase II)

how it stacks up against existing treatments for that disease (Phase III)

whether the drug has any long-term effects (benefits/side effects) and how it performs in broader populations (Phase IV, once the drug is approved)

This is a loose pathway. Cancer drug research has enabled more innovative trial designs to speed things up for ethical reasons, but we’ll save this for a future letter. For today, I think you should know that minorities, women, and older adults are underrepresented in clinical trials. We need participants in a clinical trial to reflect the demographics of the future users of each treatment. Clinical trial diversity is not just good science—it’s also a health equity issue.

WHY WE NEED DIVERSITY IN CLINICAL TRIALS

We’re a diverse bunch. This matters because chronic diseases disproportionately hit minorities. Per the 2020 US Census, we’re now more multiracial than in 2010 (SO to my fellow mutts), and 30-40% of the population is from minority groups. Our population includes 18.7% Hispanic/Latino, 14.2% Black or mixed, 7.2% Asian or mixed, and 2.9% American Indian/Alaskan Native or mixed people. An analysis of clinical trials between 2000 to 2020 found that most US trials failed to report race/ethnicity. Stats improved for studies in 2020. Of 32,000 new drug trial participants, 8% were Black, 6% Asian, and 11% were Hispanic.

Genetics can influence disease severity and/or how drugs work. You may know someone who’s had a breast cancer diagnosis, it’s the most common cancer in the US. But did you know Black women tend to be younger when they get breast cancer? They’re also more likely to have an aggressive subtype. Scientists have now linked specific genetic mutations to breast cancer risk in Black women. In other cases, genetics contribute to different treatment responses. For example, evidence implies that men respond better to tricyclic antidepressants whereas women may be better off with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Diverse clinical trials can improve drug development. Participants in cancer trials skew younger than their real-world counterparts, but older people suffer more negative side effects. The theory is that our liver and kidney functions drop as we age, making it harder to tolerate drugs. Drug response also differs between older women and older men. Diverse trials tell a more complete story on drug safety and efficacy. This helps flag negative effects that would otherwise only reveal themselves after a drug is widely available, potentially reducing development costs for pharma. Clinical trial diversity can be a net benefit, ensuring study findings are representative of the target population (generalizable).

PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES ARE EMBRACING TRIAL DIVERSITY

Clinical trial diversity is a systemic issue with many main characters, and the pharmaceutical industry is a key player. As such, the industry trade association, PhRMA, committed to enhancing clinical trial diversity, and individual companies followed suit.

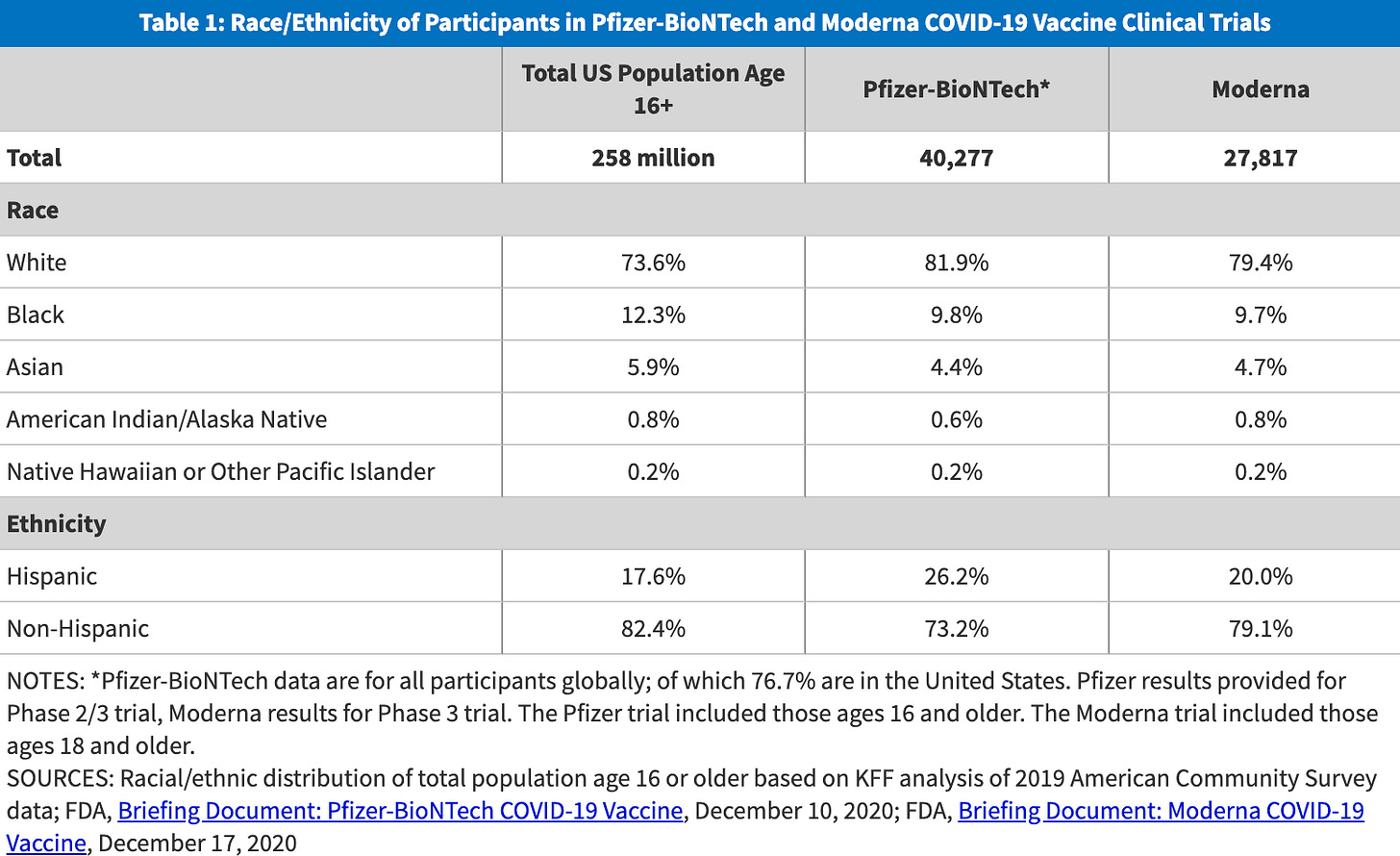

The pandemic put this to the test. Pfizer and Moderna worked hard to recruit more diverse populations for their COVID-19 vaccine trials. When they weren’t meeting targets for Black, Latino, and Native American participants, Moderna slowed enrollment to improve trial representation. Ultimately, both the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 trials were more diverse than others.

All top 10 pharma companies in the U.S. (by revenue) have pledged to diversify their clinical trials, but some still have work to do. It was interesting that Google kept serving up sponsored Merck clinical trial content though. I’m happy to expand on this IRL the next time you see me at Time Again.

The good thing is pharma companies are now comparing their trial populations from recent studies to real-world epidemiological data and finding that their demographics weren’t too far off. GSK has also reported that all of their 2023 Phase III trials had diversity action plans in place. That’s progress!

CONTRIBUTIONS TO CLINICAL TRIAL POPULATION DISPARITY

For me, access goes beyond affordability. My key business question is often, “If our drug were free, what would keep patients from accessing care?” Three main barriers are at play for clinical trials.

We’re not communicating effectively: To join a clinical trial, patients and their doctors must know that a clinical trial is even an option. Black people were just as likely as white people to agree to cancer clinical trial participation if they were aware of the trial in the first place. Yet doctors are less likely to discuss clinical trial options with minorities.

We have a trust problem: Minority groups tend to mistrust the healthcare system. It’s reasonable to mistrust a system that has used black men to see what happens when syphilis is left untreated, infected Guatemalans with syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid to test treatment options, and forcibly sterilized Black, Latina, and Indigenous women. But we’re rebuilding. Understanding unique responses across groups can help us make informed treatment decisions and foster trust in the health system.

We’re still racist (structural): People of color are more likely to receive care in under-funded hospital systems and under-funded hospitals run fewer clinical trials. Other structural issues like rigid work schedules with no PTO, travel time to trial sites, and health insurance coverage make it difficult for minorities to benefit from clinical trial participation. Access to care is also tied to diversity in clinical studies. Let’s consider colorectal cancer screening guidelines. Although Black people are more likely to get colorectal cancer, we don’t have tailored screening guidelines because we don’t have the data to back it up. The snake is eating its own tail.

HOW TO PROMOTE CLINICAL TRIAL INCLUSION

Clinical trial diversity is now a policy priority. This is a good thing. Earlier this summer, the FDA published a draft guidance on clinical trial diversity action plans. They’re on the right track.

To improve clinical trial diversity, the entire health system must work together. Regulators (FDA)/government can only do so much without bringing in tech, patient groups, academia, and pharma companies. Pharma partners like Institutional Review Boards and contract research organizations can also support diversity initiatives Working holistically, we can build trust through community outreach, set clinical trial sites in underserved areas, use AI to refine patient selection, inform patients about clinical trial opportunities, and make it easier for minorities to participate (e.g., transport, meals).

FYI, the draft guidance is open to public comment until September 26th, in case you want to let them know your thoughts.

xxsem