Powerful interests are betting we forgot about the AIDS crisis

Don't let them win

Today’s newsletter is a first-of-its-kind for Of Note. To supplement my thoughts on access to HIV care, culture, and resilience, I interviewed one of my ballet teachers! The arts are a powerful force in shaping public perception and advocacy. Read below to see how art and activism go hand-in-hand—whether you’re taking up space on the dance floor or the streets.

The threat to HIV care

The public health response to HIV/AIDS will go down in history as one of the field’s greatest hits. Globally, HIV-related causes of death (mortality) and new infections (incidence) are down, thanks to community activists, international collaboration, care providers, and drug makers who changed the HIV landscape. Yet, Massachusetts flagged a cluster of more than 200 new cases since 2018 while West Virginia, Indiana, and Ohio also faced HIV outbreaks. While HIV hasn’t been a death sentence since Gen Z entered the stage, our current US health policy climate threatens access to HIV care.

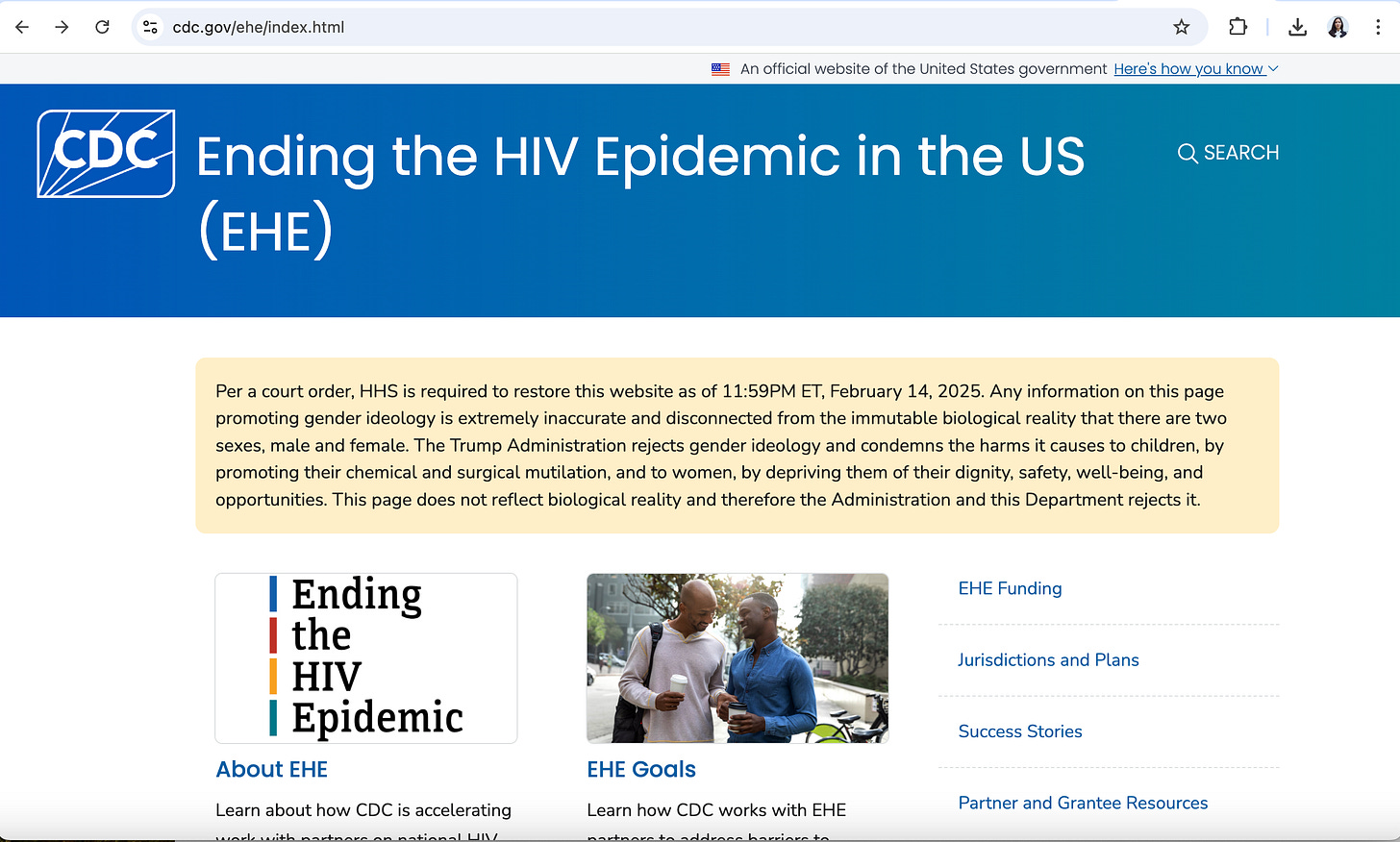

Over shared plates at Girl Dinner™ restaurants (see: Bar Valentina), friends share their concerns over cuts to HIV services in the US and abroad. The overall sentiment is that many people will die. PEPFAR, a George W. Bush program with strong bipartisan support that has saved 25 million lives and reached 20.5 million people via HIV testing and care access (including PrEP) is in jeopardy. DOGE also attacked USAID, which is a top player in tuberculosis prevention. This matters because USAID’s role in preventing infectious diseases around the globe also protects the US and tuberculosis is one of the top killers of people living with HIV. Our role in global health protects American interests. Sometimes, I feel like I have whiplash because the last iteration of Trump’s administration prioritized HIV prevention in the US. He even launched the Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) initiative, aiming to reduce new HIV infections by 75% by 2025 and 90% by 2030 by targeting the highest-burden regions and populations in the US. We’re nowhere near meeting this target, and it seems like his new admin has abandoned the program. I visited their website and found this notice:

My read of the Trump 2.0 Administration: They’re betting big on our collective amnesia. I’m resisting this by patronizing the arts and giving my time and money to causes close to my heart. But the data is on their side. While 90% of Americans say they know a bit about HIV, only 37% of Gen Z report being knowledgeable. Art and visibility matters when it comes to breaking stigmas and saving lives. We lost a large part of our cultural heritage as HIV/AIDS wiped out an entire generation of queer artists, dancers, and musicians. What more could visionaries like Alvin Ailey, Robert Joffrey, Michael Bennett, and Keith Haring have done? We’ve missed out, let’s not let this happen again.

In dialogue with Julian Donahue

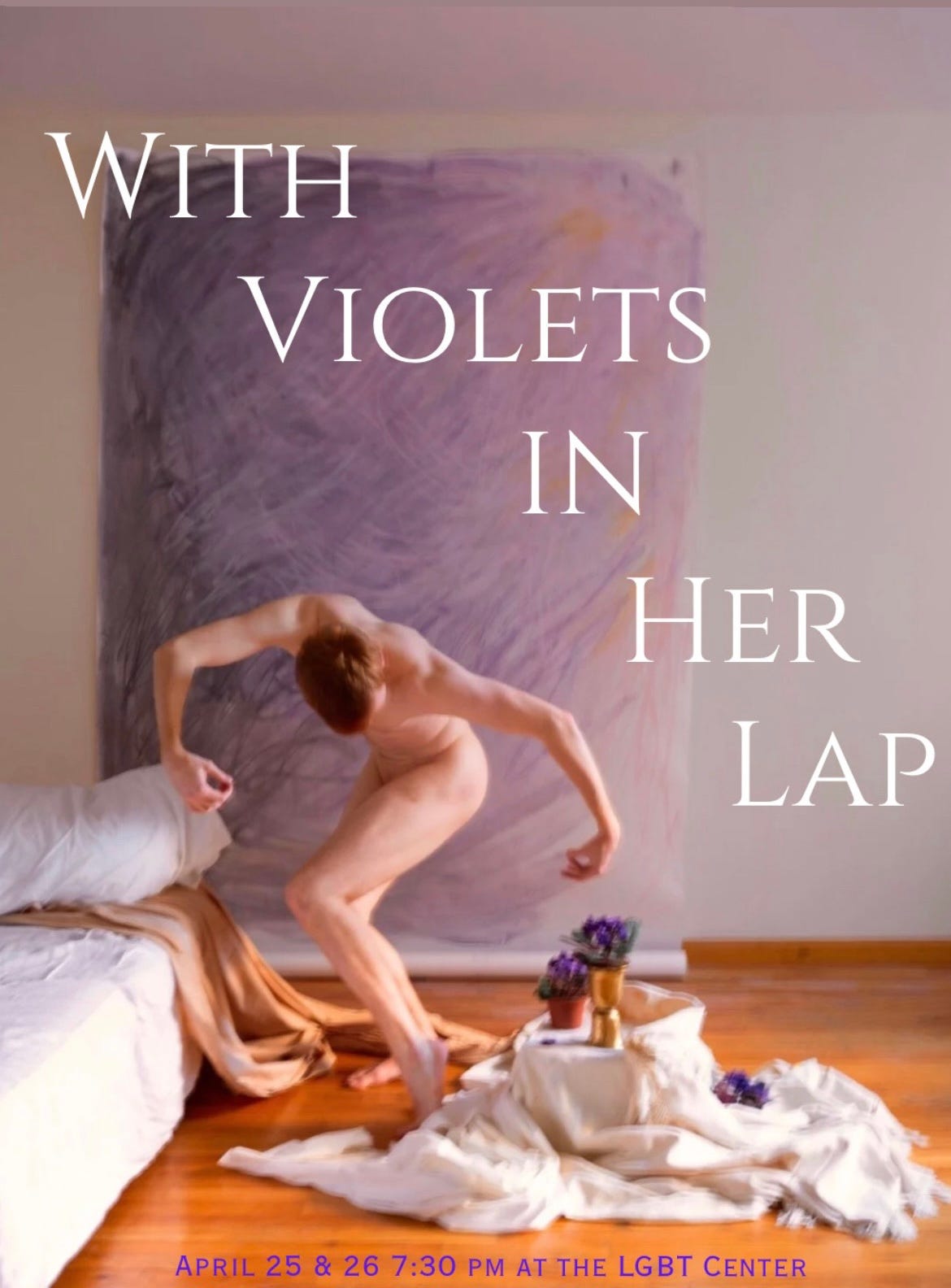

As my tiny act of resistance, I attended last night's premiere of Cornfield Dance’s The Endless Ladder. Julian Donahue, a choreographer who happens to be one of my ballet teachers, performed. I took the opportunity to ask him about his upcoming one-man show, With Violets in her Lap. Here is an excerpt from our chat.

I’ll be at his fundraiser at Singer’s Bar on March 18th. If you want to say hi and buy me a drink, RSVP here.

Can’t make it? Call your representatives! And contribute to Julian’s show’s production here.

What inspired you to create this show? Was there a particular moment that sparked With Violets in Her Lap?

I had the original idea for this show 6 years ago, when I was still in college: a requiem for all the queer people lost to AIDS. But at that tender age I don't think I had the personal or artistic gravtias to tackle a project with such depth. I always say that art for me is like a buildup and a purge. An idea lives in me until it has gestated and begs, kicking and screaming, to come out into the world. Last year, I experienced the first serious push that now was the time. Then the 2024 election happened and this project became even more relevant and timely.

You describe the loss of the AIDS generation as a “void” in queer lineage. How has embodying that absence through dance changed your personal connection to queer history?

The void and I have a complicated relationship. The concept comes from a quote from queer architect Aaron Betsky: "The queerest space of all is the void, and AIDS has made us live in that emptiness, that absence, that loss... it is not a queer space any of us would want to inhabit, but many have been forced to make it their own." Early on in this project I experienced the void as a kind of absence of queer ancestry. A whole generation lost to AIDS that means younger queer people don't have as many queer mentors. But this project has brought me closer to so many queer people of all generations in my life, and many new friends. I'm conscious now that the void can be an illusion, there is still community. I'm also conscious that it's important to look deep into the void, because it's not just a black hole, each individual lost to AIDS is a uniquely shaped, and irreplaceable void in the world and the queer cultural fabric.

Can you talk about your process for choosing the music for this piece?

The original idea I had in college was to use Mozart's requiem. As I read more about AIDS and queer resistance it became very evident to me that this period was not all loss and depression, it was also joy, celebration, anger, desperation, relief, community. Listening to the requiem there are movements that sound like relief, or joy, or anger, not just sadness. I've always been fascinated by disco music because of it's association with joy and celebration. But there is a melancholic quality to disco. Often the lyrics are gut wrenching while the beat is dancey and uplifting. Sylvester died of AIDS in 1988, and on his deathbed thanked his fans and the queer community for giving him his life. This idea of life and death being closely related, mourning and celebration being almost the same act, is a foundational idea to this work.

You’ve drawn from a diverse range of movement styles—from Cecchetti ballet to Baroque and Renaissance dance. How are you weaving these influences together to tell this story?

The study of historical dance has taught me that our bodies carry history. This show makes the point that AIDS has left the queer community with a generational trauma. Even though the folks who died of AIDS in the 80s and 90s are not my biological ancestors, they are my cultural ancestors. Weaving together different dance styles helps show the audience the way our bodies can be vessels of different histories. For a very informed dance audience, viewers may notice specific allusions. For someone who isn't a dancer, one may see the collage aspect of my choreography: a lot of different styles in one big melting pot.

What was the most challenging part of embodying this history? Have any moments in rehearsal surprised you?

The most challenging part is taking on a subject that is traumatic to so many. I am keenly aware that this moment in history has deeply hurt so many people. The last thing I want to do is make people relive something they've closed the door on. But that's why it's so important for people to understand that this project is not a history. This project is a reflection on the way the AIDS crisis lives on in the queer community of today. As someone born in 1997, thought to be the last year of the AIDS crisis in the US, when protease inhibitors became widely available, I experienced AIDS as a slur, a bullying tactic. Growing up bullies would say "You're a fag. You're gonna die from AIDS." When someone close to me received a false positive diagnosis, on top of the difficulty of dealing with a medical system that didn't know how to proceed with that diagnosis, all the trauma of being told for years as a kid that this would be your death sentence came back like a flood. At the Works in Process showing, I showed two sections from the show and engaged in conversation with the audience. A surprising moment was the way talking about this work seemed healing for me and for audience members. Conversation will continue to be an integral part of this project

The show features an entr’acte by Lavender Menace. How does drag fit into your exploration of queer ancestry and memory?

I am fascinated by drag for its ability to link chaotic ideas by being both entertaining and confrontational. Drag also inspires me because it's an art form in which one artist comes to represent their community. Drag artists are often the loudest and most visible supporters of our community, which they accomplish by standing firmly in their individuality. As a one man show, this project takes a deep inspiration from that history of queer performance art.

This show isn't aiming to represent the AIDS crisis, but is instead your personal search for queer ancestors. How do you see that personal storytelling as a form of activism?

The AIDS crisis was a genocide of government inaction. The ultimate goal of genocide is not just to kill people, but to erase memory. Genocide is a losing game, because they can never kill memory. Memory lives in our bodies and in space. My life has been touched by the crisis: whether it be the bullies who use AIDS to threaten me with early death, whether it be the void in the fabric of queer lineage, whether it be the spectre of losing access to Prep and HIV funding today that would thrust us back into a full blown HIV/AIDS crisis. In college I studied dance and political science. This project has shown me once again how those two disciplines are connected. Putting on a show is an exercise in community building and community engagement. Telling this story through dance has been a deeply communal experience, building queer power through queer art. I owe so much inspiration to ACT UP, Gran Fury, the Marys, and drag artists.

The AIDS crisis profoundly affected the dance world, with choreographers and performers lost before their time. How do you think that loss still echoes in the dance community today?

One aspect of the void is cultural. V (formerly known as Eve Ensler) talks about how the AIDS crisis took out so many folks who existed on the fringes, who had radical ideas, who thought, acted, dressed, danced, differently. Sarah Schulman calls this the gentrification of the mind. We will never know those dancemakers who never got to show their masterpiece, or those dancers who never got to perform the role that would make them famous. Alvin Ailey's legacy is immense and impressive despite his untimely death, but how many more dancers and young choreographers could have been touched by him personally if he hadn't been taken from us? These are questions that will never be answered, and that's the void. It is a loss of life, a loss of culture, a loss of community, a loss of lineage.

What do you hope young people—especially those who may not have engaged deeply with this history—take away from your performance?

I hope they look into their lives and investigate how the AIDS crisis has affected their young lives. Gen Z people grew up in the spectre of all this death. We did not live it, but we grew up in the aftermath. The body knows that and feels that, and so it is a trauma waiting in us. I hope young folks, old folks, and everyone in between come to the shows, or to events leading up to the shows, and turn to their neighbors to hear their stories. March 18th we will have a fundraiser and consciousness raising celebration in Brooklyn at Singers Bar. And stay tuned for an April event in the works: an intergenerational conversation about AIDS, loss, and being queer in today's world.

As a Gen Z artist, how do you see your work contributing to the ongoing lineage of queer storytelling through dance?

I am beyond inspired by the guts of so many queer artists. Inspired by the drag artists and trans folks of the 1960s and 1970s who wore the clothes they wanted risking arrest; inspired by the Marys who refused to let the deaths of their friends be a silent mourning but instead brought the bodies into parks, into the streets, and to the front steps of a fundraiser for President Bush Sr.; inspired by Sylvester who made gut-wrenching and booty bumping music that spoke to life and death; inspired by John Kelly who spoke to me about fairy dust; inspired by all the queer artists who took to the streets and took action. Some parts of this project are gutsy, and I hope, humbly, that it encourages other Gen Z artists to be gutsy, loud, brash, and confrontational, because they're coming for us whether we like it or not.