The doctor won't see you now

the US health system is broken, and so are we

Today, we cover the physician shortage, an often overlooked health system topic. But I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge current events in the US healthcare payor space. Specifically, the seemingly targeted killing of a health insurance CEO + another payor’s proposed changes to anesthesia payments (which was later reversed).

Gunman kills health insurance Chief Executive in Midtown Manhattan, benefits from pretty privilege

You likely know by now that someone fatally shot a health insurance chief executive in Midtown Manhattan this week. It’s one of the most unifying moments online in recent history as people celebrate his death. People on Twitter are going feral for the suspect after his maskless photo revealed he may be kind of hot. While callous, this rage underscores that people want lower healthcare costs. People are fed up with the status quo. Resentment and helplessness breed hostility. It resonates with a question by Shumon Basar that Rian Phin cited earlier this week (for completely unrelated reasons, she was analyzing the Prada SS25 show!): “As we become less powerful, do we become more extreme?” At the same time, I don’t think CEO public executions are cause for celebration. This man has a family. We also don’t know the exact circumstances that led to his murder. Was he the worst actor or a scapegoat? I asked a friend who works for a smaller not-for-profit payor how her colleagues responded to this news. It turns out death threats are just part of the job description for health insurance execs. God Bless America, but we can’t fix a broken health system with gun violence!

Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield tries + fails to lower health costs by changing how they pay for anesthesia

Last month, Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield announced a plan to change its payment structure for surgery anesthesia services early next year. In a flawless show of controlling the narrative, the American Society of Anesthesiologists called for “Anthem to reverse this proposal immediately.” They accused Anthem of putting profits over patients by refusing to pay for anesthesia if the surgery runs longer than “an arbitrary time limit.” Of course, everyone jumped on the commercial health insurance hate train. Dr. Glauomflecken (ophthalmologist med-fluencer) posted a TikTok role-playing as a greedy insurance exec and his well-intentioned direct report. He echoes the sentiment that the insurance company will set a random time limit per procedure based on vibes. 30 minutes for a kidney transplant—“just pop it in!” The UHC chief exec shooting added fuel to the fire. Taylor Lorenz quote tweeted to a PopCrave tweet about this with a screenshot of Blue Cross Blue Shield’s CEO + name. You should know I'm historically a Taylor Lorenz apologist, but I think this was a dangerous thing to post. I imagine she agrees because she’s now removed it.

Anthem has since decided not to move forward with this change, citing feedback (read: public outcry) and misinterpretation of the policy. Someone needs to write a dissertation on this because it shows how limited health policy understanding could hinder cost-containment efforts even when health insurers aim to do good for the health system. Anthem redacted their original statement and replaced it to avoid confusion, but I found it on archive.is. What did the proposed policy actually say?

“We will use the CMS [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] Physician Work Time values to target the number of minutes reported for anesthesia services. Claims submitted with reported time above the established number of minutes will only pay up to the CMS established amount.”

This excludes cases where the patient is under 22 years old and any maternity-related care. TL;DR: Anthem wanted to pay doctors closer to what CMS pays by anchoring to CMS average service length. I’m not getting into the weeds of anesthesia reimbursement, but CMS tends to pays less than commercial health insurers. However, they don’t stop paying if a procedure runs longer than average. In a Twitter thread, Loren Adler shared that the policy change may let Anthem deny the entire claim if billed above average time, placing the burden on the anesthesia provider group to appeal. But it wouldn’t really have impacted patient pay, as the change would only affect the negotiated rate paid to providers. (Psssssst: In-network doctors can’t charge patients anything over the contracted rate.) I talked with two anesthesiologist friends about this. They have nothing to do with how things are billed (duh, most doctors don’t), but they said procedures often run long for things completely out of their control. Like when surgeons accidentally cut into an organ or forget surgical gauze/towels inside the patient. Or a patient has a full stomach. Or is on blood thinners or smokes. Et cetera! My view is that Anthem was trying to curb fraud, specifically where anesthesiology groups upcharge for work not done. Like I said, we can all agree the US health system is broken.

Speaking of which, we don’t have enough doctors.

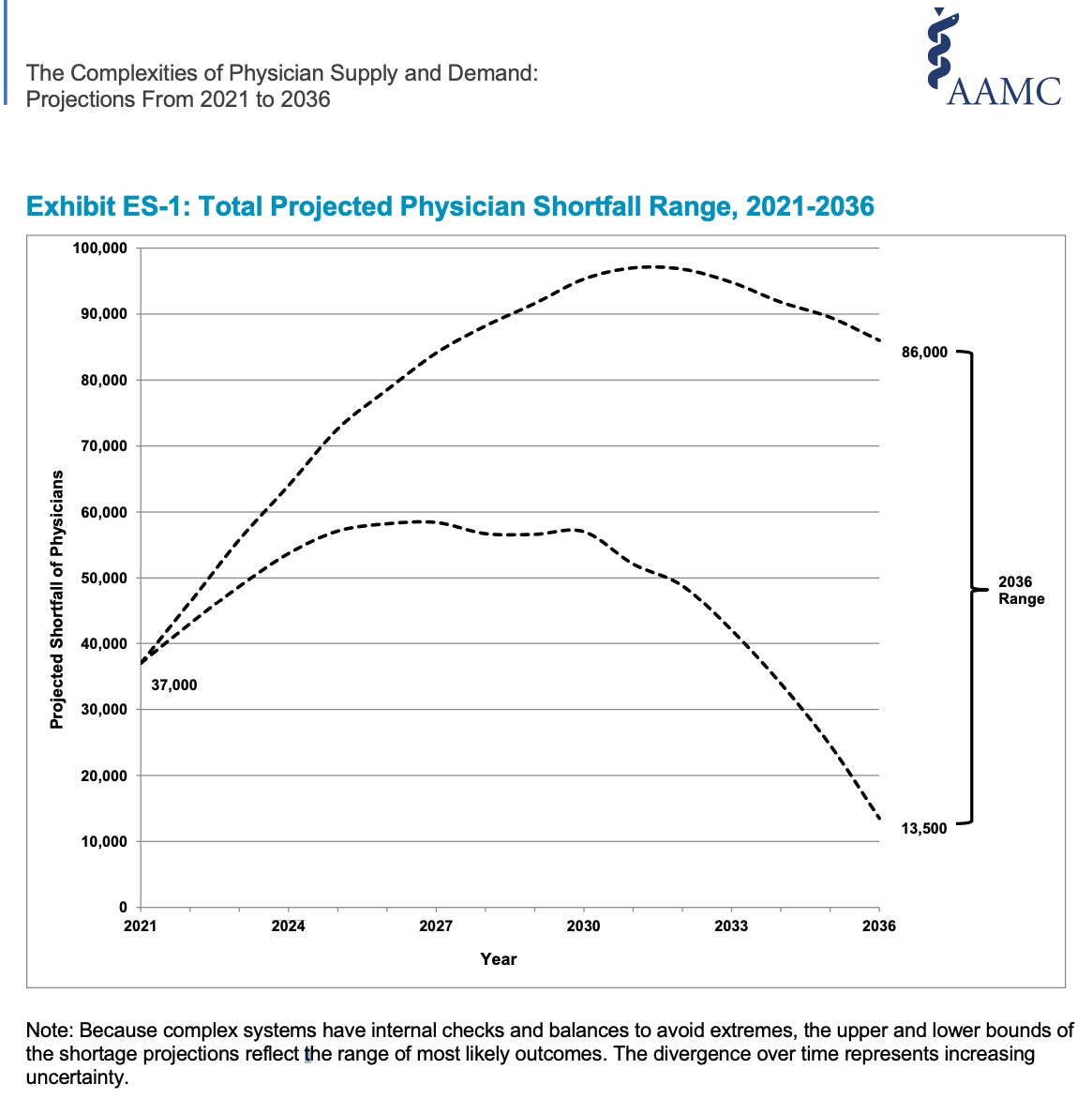

As part of my job fostering innovation-friendly environments (i’m available 4 hire!), I’ve worked with in-country brand colleagues to assess the health of their health system. Among other things, I always asked about resourcing: “How many doctors in x therapy area practice in your country per 1,000 people?” It’s one of many 'health service readiness’ factors. This matters because it can ensure people get diagnosed early, are given the right level of care, and have a better shot at survival. Per capita, the US has fewer primary care physicians than most other OECD countries. By the time we ring in the new year and toast to new versions of ourselves, we’re projected to be short up to 64k doctors.

By 2036, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) says we may be missing up to 86k doctors in the US. They anticipate primary care will be hit hardest, which sucks for us because primary care physicians are key to population health. A higher supply of primary care physicians yields better health outcomes, lower mortality rates, and better chronic disease management.

WHAT’S CAUSING THE SHORTAGE?

We’re getting older + living longer. This is a two-part issue. In general, older people need more care than younger people. We’re living longer, so we have more older people who need care. This also means doctors are getting older! Per the AAMC, 20% of current working doctors are 65 and older, and 22% are 55-64 years old. Meaning many will retire in the next ten years.

Doctors are overworked + bunt out. This isn’t new and precedes the pandemic. But COVID-19 threw fuel on the fire. In addition to high patient loads (from doctor shortages, it’s a positive feedback loop!), long hours, and emotional stressors on the job, they also face administrative hurdles (like fighting with insurers). They’re doing more work for stagnant or dwindling pay. Some doctors have left medicine, others have ended their lives entirely. This year, residents in several training programs have gone on strike for higher pay and better working conditions—including the University of Buffalo and George Washington University.

Supply reduction happens early, starting in medical school. Medical school spots are limited. We don’t have that many accredited MD or DO programs, and they’re highly selective. The 200+ student biology and chemistry classes I took at UCLA were considered “weeder” classes, meant to cull the number of pre-med students by breaking them down until they pivoted to other fields of study. We also only have limited residency spots and senior physicians to train junior doctors. Most residency spots are federally funded as Graduate Medical Education through CMS to cover Medicare patients and supplemented through state and private funding.

WHY DOES THIS MATTER?

Doctor scarcity limits our access to quality care and drives up healthcare costs. This will be even worse for rural areas already struggling with access to care. For OB-GYNS (often, they serve as women’s primary care providers), political and regulatory changes are an added pressure. We’re already short on OB-GYNs, which will only get worse with scaled-back abortion services protections. The American Medical Association reported a lower number of OB-GYN residency program applications in abortion-ban states. In Texas, established OB-GYNS are fleeing the state with the criminalization of the standard of care for things like miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies. A friend of a friend is an OBGYN in [redacted] state and says the worst thing about our physician shortage is that shitty doctors don’t get kicked out of their residency programs. Why? Because there’s no one to replace them. This is a recipe for disaster.

WHAT’S THE POLICY PLAY?

This is where I once again tell you that we need to take a multi-disciplinary approach to solve this problem. It can’t just be policymakers. We need to bring in care providers who are intimately familiar with real-world clinical practice, patients and their caregivers who navigate the health system and are directly impacted, and payers who cover these services. So what can be done?

Increase medical school capacity and residency positions

Expand the scope of practice for non-doctor providers like nurse practitioners and physician assistants to fill the gaps, where reasonable

Use telehealth + tech to close the gap and reduce variance in access to care (including in rural areas).

Improve working conditions for physicians (admin burden, pay, scheduling, etc.)

Make health insurance more affordable/accessible so people aren’t delaying regular check-ups with a primary care doctor and using their local ER as a stopgap measure

Treat people as humans

xxsem