Why don't all clinical trials use placebos?

placebos won't fix him, babes

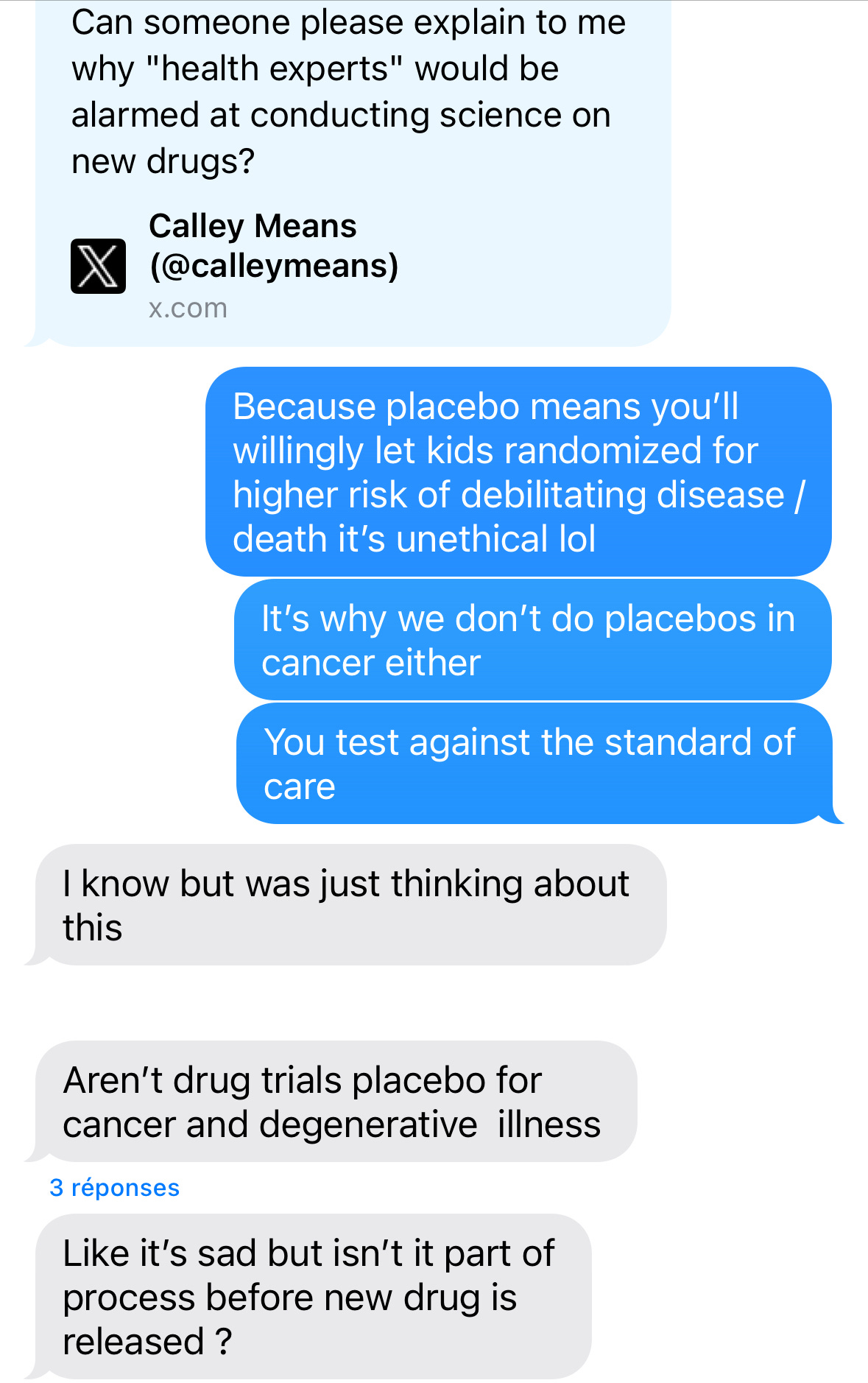

Last month, in another blow to vaccine confidence, HHS/RFK Jr. announced that they want new vaccines tested against placebos. That pissed off some medical professionals. In response, Calley Means asked: "Can someone please explain to me why ‘health experts’ would be alarmed at conducting science on new drugs?” The administration defended it as a win for vaccine safety, claiming none of the vaccines recommended for children were ever tested against placebos. This is false. To prove their point, infectious disease doctors pulled out the receipts: a crowdsourced list of placebo-controlled vaccine trials. Later, a smart, curious friend of mine (who may be a little skeptical about vaccines) texted me about this. And it made me realize that what feels like basic science to me can be totally esoteric to others.

So this was a lesson in grace. No one can know it all, which makes life fun. So, let’s spend some time on the placebo question. When are they appropriate? When are they not? By the end of this letter, you can all make an INFORMED decision on whether or not this is good policy. I love teaching men to fish.

Let’s back it up, what’s a placebo?

A placebo is an inactive treatment meant to mimic the real deal (active treatment), but it’s cap. In clinical studies, researchers can compare how trial participants respond to active treatment vs placebo to measure effectiveness AKA how well the drug achieves its intended effect. For example, sugar pills for trials assessing oral treatments or saline for studies where active treatment is injected/delivered intravenously. Using a placebo that looks/smells/tastes like the active treatment limits bias in trial results by reducing the risk that participants figure out whether they got an active treatment or an inert placebo.

When are placebos appropriate?

Randomized, placebo-controlled trials are widely considered the GOAT of evidence-based medicine. In the simplest terms, participants are randomly sorted into equal groups (treatment arms) where one group gets an active treatment and the other, a placebo. If it’s double-blinded, neither the participant nor the researchers know who’s getting what. If it’s single-blinded, the researchers know, but participants don’t.

Let’s take a look at vaccines. Placebos are good when testing new vaccines for new pathogens (e.g., RSV, COVID-19). The COVID-19 vaccines, for instance, were tested against placebos. We had nothing else to compare them to. Once scientists establish a foundation of vaccines that work, they test new iterations against existing vaccines.

When NOT to use placebos?

We can’t give someone a fake drug when a real one could save their life. This is especially the case for cancer, infectious diseases, and rare diseases.

Placebos are uncommon in cancer clinical trials. Most studies compare a new treatment to an approved one because keeping sick people from cancer care is unacceptable. Why give patients fake drugs when the risk is death? In a double-arm trial, one group gets the investigational drug (new treatment), and the other group receives the next best thing (existing standard of care). If the new drug performs significantly better, it may usurp the existing drugs to become the new standard of care. In the rare cases where placebos are used, it’s usually one of two reasons:

First, when the new drug is added to an existing drug, and you want to vibe check the contribution of each drug in the combination. If the active treatment arm tests the new therapy plus standard of care chemo, a comparator arm would use placebo plus standard of care chemo.

Second, when researchers are studying a cancer without approved treatments. In these cases, physicians may take a “watch and wait” approach, so placebos are fair game.

New vaccines for diseases with existing vaccines are usually tested against those vaccines in “bridge” studies. I’m not a vaccine expert, but my understanding of bridge studies is that they assess whether a vaccine candidate (new vaccine) and an approved vaccine trigger your immune system in the same way. We want enough of an immune response to build antibodies for future pathogen exposure. Bridge studies build on historical studies where older vaccine generations were tested against placebos to determine whether they’re worth bringing to market. As with cancer, it’s unethical and irresponsible to knowingly expose trial participants to the risk of debilitating illness/death when we can avoid it.

How can we account for situations where placebos aren’t appropriate?

I love this topic because I love novel trial designs and Real-World Data. When it’s unethical or impractical to run randomized placebo-controlled trials, researchers have the option of using single-arm trials. They’re pretty self-explanatory: there’s one group and they all get the investigational product. We see these a lot in areas of unmet need (think: cancer, rare diseases). If you’re thinking this isn’t enough evidence, congratulations…you’re already thinking like a scientist. We address this evidence gap by building artificial control arms using Real World Data (claims data, electronic health records, registry data) and comparing them against trial results. Some countries are more accepting of innovative trial designs than others. Both the FDA and EMA accept single-arm trials for regulatory approval. Sometimes, with the promise to collect more data once the drug is on the market. But it can be more challenging when asking insurance companies and payers to reimburse the drug (we can get into this in a future letter).

Knowledge is the antidote to paranoia

The fun thing about science is it’s always evolving. You don’t need a fancy degree to understand this stuff, just a dash of curiosity and a healthy dose of context. Placebos are powerful tools, but they’re not always the right ones. What do you think?

xxsem

Another Great Read!