Why we don't have universal health coverage in the US

let me hold your hand while i say this...

Before I get to that, I have an update for you! In my mission to become God’s favorite Key Opinion Leader, I launched a podcast with two of my favorite healthcare business insiders: Emily C. + Ariana M. We called it The Worried Well, a term for those who are healthy but are preoccupied with fear of becoming ill. They’re well but suspicious about it. We all know them, and we all love them. Look no further than your friend who lives and dies by their Oura ring or attending the “Don’t Die Summit” at Javits Center today. Policymakers and insurance companies hate their healthcare resource utilization, but we can cover that later. You can listen to our first episode here if you’re on Spotify and here if you’re not. Onward!

So, why don’t we have national health insurance?

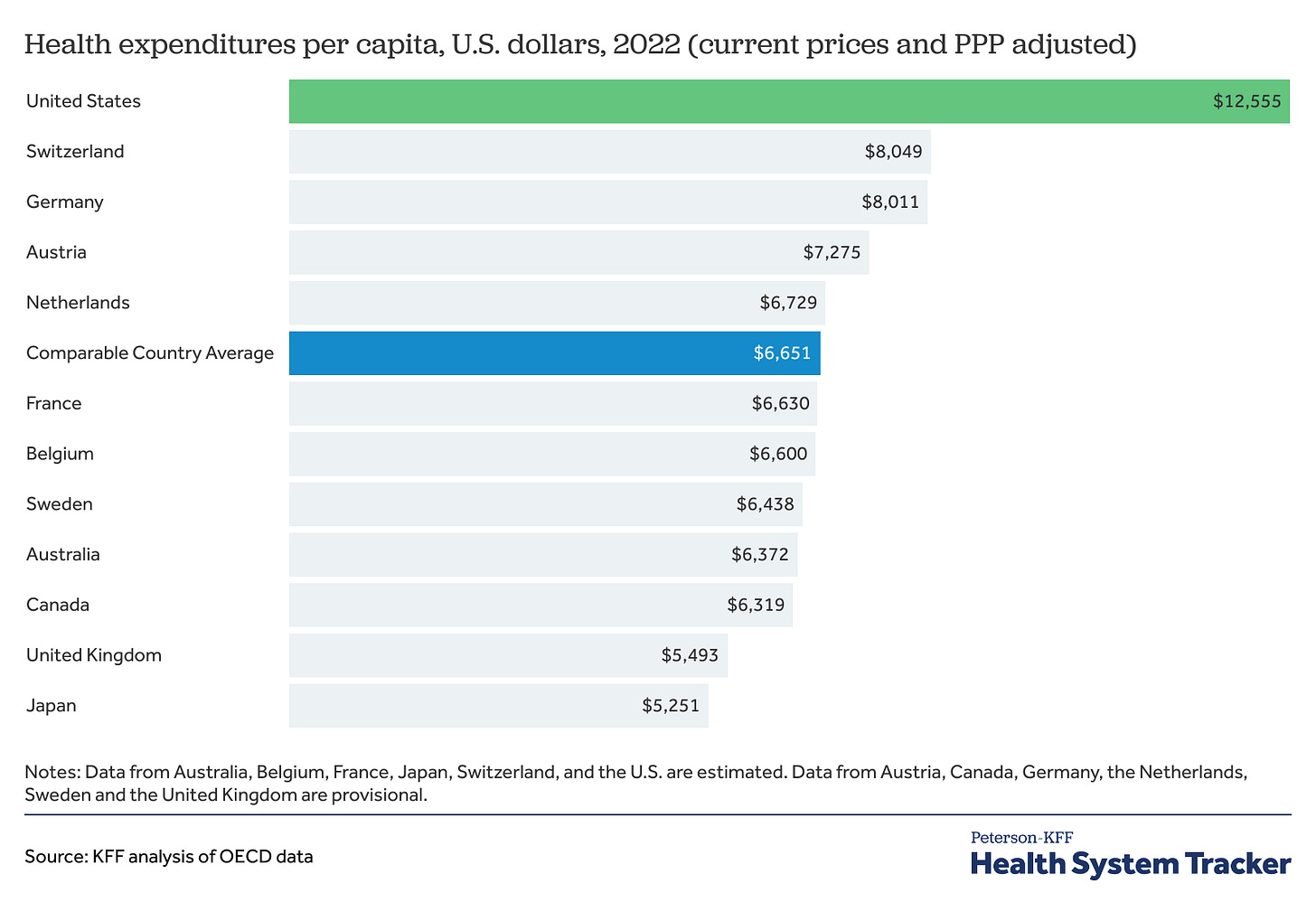

If your brain is fried or your attention span is short, the simple answer is that the American Medical Association (AMA) is to blame. But nothing happens in a vacuum. We don’t have universal healthcare because it’s not the American way. Our political system, economic priorities, cultural attitudes toward healthcare, and diverse population keep our ailing health system from flatlining. For decades, experts have warned that we spend far more on healthcare than other wealthy nations without seeing better health outcomes. While all rich countries invest more in healthcare per capita than low-income countries, we spend nearly 2x per person and have a lower life expectancy than other high-income countries. Many factors drive this: we are the richest (#1 by GDP, though we fall behind countries like Luxembourg + Switzerland when adjusted per person), have better, faster, stronger specialized health technologies, pay doctors more than other countries, and practice defensive medicine.

Is the American healthcare system just four cats under a trench coat?

Depends on who you ask! We have a mixed healthcare system of private and public (gov-funded) insurers and healthcare providers.

We borrow from Germany’s Bismarck model for our employer-sponsored commercial insurance system and private care delivery. That’s when you get your insurance from your employer. They cover part of the cost and deduct a portion from your paycheck.

We also have a tax-funded insurance that iterates on the British Beveridge model and covers the Veterans Health Administration, the Indian Health Service, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

Some of us technically do have single-payer national health insurance, with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services acting as the government payer for citizens 65 and older and/or disabled. Still, care is mostly delivered in private settings. Medicaid covers low-income earners and is jointly funded by states and the federal government. If you’re ever confused between the two, know that we care for the elderly—Medicare—and we aid the poor—Medicaid.

Those not covered by the above fall under the out-of-pocket and/or uninsured model by default. When people who can’t afford health insurance but make too much money to qualify for Medicaid show up at Emergency Rooms and can’t cover their bills, they still receive tax-funded healthcare. As non-profit entities, hospitals don’t pay taxes, and our Federal taxes help hospitals offset their unpaid patient bills. However, continuity of care is expensive and harder to access (especially if they need referrals to specialists or higher-tech care). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded Medicaid and subsidized Marketplace plans to lower the number of uninsured people, but we still had 25.3 million uninsured people in 2023. For reference, we had about 47 million uninsured people pre-ACA.

How did we get here?

Political priorities + interest group influence

Our sweet angel President Teddy Roosevelt (famously sympathetic to both business + labor) wanted health insurance for the working class. He failed to bring this dream to life, but he understood that investing in the health of American citizens was an economic investment in the country. After the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought to expand social services through the Social Security Act. Although he wanted to include national health insurance, he deliberately omitted it to avoid jeopardizing the law’s passage.

World War II opened a national health insurance window of opportunity in the US. We elected the pro-national health insurance Harry Truman as President and equipped him with a Democratic-majority Congress at a time where public opinion on national health insurance was high. Truman, like others before him, understood that healthy human capital is priceless. Unlike his predecessors, he wanted single-payer, tax-funded health insurance for all. Truman’s plans failed due to a strong oppositional force that swayed public opinion by debasing nationalized healthcare as un-American and as socialism (Cold War America’s biggest fear).

The opposition in question? The American Medical Association. The AMA initially supported compulsory health insurance but quickly turned into its biggest hater. To counter Truman’s efforts, the AMA charged each member an extra $25 and used those funds to throw shade at national health insurance. This was an unprecedented political smear campaign designed to stop Congress from passing nationalized health insurance and steer Americans toward private, voluntary health insurance. The AMA framed nationalized healthcare as a threat to doctors’ profits and autonomy, which was ironic given that the AMA was founded to regulate medical labor and bring order to what was once the Chaotic Wild West of Medicine. Of course, the AMA’s efforts in licensing doctors and standardizing medical education have protected patients from harm, but physicians haven’t operated with complete autonomy since 1847. In a genius marketing ploy, the AMA framed private insurance as “freedom” (are you hearing the U-S-A chants, too, or is it just in my head?) and used mass advertising, physician outreach, and congressional lobbying to shift public opinion against national health insurance. We didn’t get Single-Payer For All, but we eventually got Medicare and Medicaid. One thing I like about this story is that when Lyndon B. Johnson signed Medicare into law, he honored Truman as “the real daddy of Medicare.”

Before we proceed, I’d like you to know that the AMA now has a more neutral stance on nationalized health insurance, as younger doctors are pushing back and gaining ground.

Population size + heterogeneity

In homogenous countries like Switzerland, where I (a mutt) can change the local race demographics by going on a work trip to Basel, achieving universal healthcare for their 8.8 million population is easier. In contrast, 340 million people of different races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds live in the US. It may have been easier to convince people that nationalized healthcare fits within the American value system if we suspended racial and/or class bias.

Cultural attitudes toward healthcare

Culturally, Americans tend to value individualism and self-reliance. Most of you know that our European allies prioritized nationalized healthcare in post-war eras. While the UK was rolling out its National Health Service, the AMA was flipping public opinion—convincing middle-class Americans to buy privatized health insurance instead. This helped sew together the patchwork system we have today.

An old grad school professor of mine used to say that the “American medical-cultural nexus is ‘more is more.’” I think he was right. Americans demand the best care, the latest technology, and every available treatment. Is this possible in a nationalized system? Many Americans are skeptical that the government can run healthcare efficiently, which is obvious when I see celebratory tweets on the DOGE team weakening federal health agencies and freezing funds. This mindset makes health reform difficult and reinforces the status quo. When single-payer, tax-funded healthcare is painted as un-American, overhauling the system to help marginalized communities is a hard sell.

TL;DR:

We have a mixed healthcare system because of historical choices, public skepticism about government involvement, and corporate influence. I am hopeful that as more people start seeing population health as an investment, we will find ways to improve access to care for those who need it.

xxSEM

P.S., This is a letter to every one of you who ask me this question each month. I love your curiosity!

Great article Susana, thanks for writing this! There’s always lots of talk about the American medical system, but the reasons we ended up here seem to always be glossed over/misinterpreted (People thinking the insurance lobby is solely to blame!) Excited for the podcast :)